Blamed by many for the 2008 financial crisis, structured finance is often thought of as a latter-day invention. In fact, these securities in “elemental form” first appeared more than 200 years ago in the Netherlands, according to a new book on financial market history edited by 2 academics at Cambridge Judge Business School, University of Cambridge.

The book, ‘Financial Market History: Reflections on the Past for Investors Today’, contains many lessons for modern investors from the history of financial markets – ranging from stock market bubbles linked to speculative German mining shares in the 15th century, to currency speculation from the Middle Ages onwards.

Published by CFA Institute Research Foundation in conjunction with Cambridge Judge Business School, the book is edited by Dr David Chambers and Professor Elroy Dimson of the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management at Cambridge Judge Business School.

“Since the 2008 financial crisis, there has been a resurgence of interest in economic and financial history among investment professionals,” Dr Chambers and Professor Dimson write in the Preface to the book.

The 304-page book flows from a symposium at Cambridge Judge that brought together many of the world’s leading academics in financial market history and 30 senior investment professionals, to discuss: “What do practitioners need to know about financial market history?”

“One central theme from the workshop was that the growth in meticulous scholarship by financial economists and historians has led to many more long-run data sets becoming available on a broader range of financial assets and countries,” says Dr Chambers, Academic Director of the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management.

“Practitioners need to resist the temptation simply to download any historic time-series when modelling risk and return, without thinking about the quality of the data and the care with which the series has been compiled,” adds Professor Dimson, Chairman of the Centre.

The book comprises 4 sections: historical risks and returns on various assets, the development of stock markets, bubbles and crises, and the role of innovation in financial markets.

The first section, “Risk and Return over the Long Run”, examines the long-term returns of stocks, bonds and other assets for 23 countries over the 116 years since 1900, as well as how those returns have varied over time. This section also offers long-run perspectives on currency speculation and the returns to durable assets (real estate, collectibles, precious metals and diamonds).

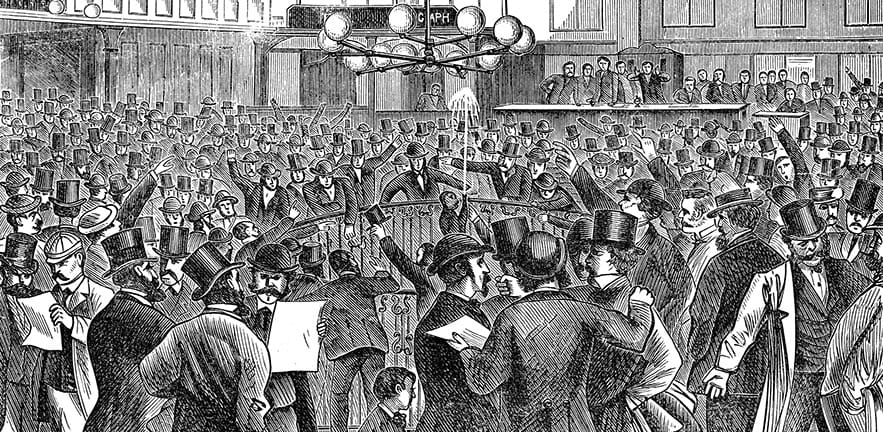

The second section, “Stock Markets”, includes historical overviews of the role of stock exchanges, market liquidity and initial public offerings. “Although the technology of trading has changed dramatically since the emergence of global financial markets in 1871, the essential conflicts between bankers and investment management firms on the one hand and stock traders on the other have not changed,” Stephen Brown, Executive Editor of the Financial Analysts Journal, writes in the book’s introduction. Sometimes history surprises us. For example, IPO underpricing so common today was not a feature of markets a century ago.

The third section on “Bubbles and Crises” provides investors with a survey of the major bubble episodes, emphasises the particular role played by irrational exuberance, and highlights the most important takeaways for investors to consider when the next bubble comes around. It also points out that financial bubbles are extremely rare events. We should be careful when drawing historical inferences as not every boom results in a market crash, so it’s important to know about bubbles that don’t burst because “avoiding them unnecessarily will lead to poor investment outcomes.” The chapter on financial crises stresses that it is equally important to study the factors that prevented the crises that never materialised as much as those that led to the crises that we actually observe.

The fourth section, “Financial Innovation”, discusses important historical episodes illustrating how innovation has been fundamental in driving forward the development of financial markets. Such examples from 18th century Dutch financial history include structured finance in the form of the securitisation of mortgage loans to West Indies plantation owners as well as the first mutual funds.

In designing these new financial instruments, merchant bankers appear to have understood many concepts used in modern finance, including the notion of diversification, value investing, the importance of collateral, investor preference for positive skewness, and agency conflicts associated with delegated money management.

There are also fascinating accounts of the emergence of specialist venture capital investors in the United States in the mid-20th century, and of the development of institutional investment in the UK and the US over the last century and a half.

The Research Foundation of the CFA Institute, which offers the Chartered Financial Analyst certification, has also recorded a series of interviews with contributors to the book, which will be made available on their website.

Featured faculty

Elroy Dimson

Professor of Finance

Chairman of the Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM)

David Chambers

Invesco Professor of Financial History

Co-Director of the Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM)

Featured research

Chambers, D. and Dimson, E. (eds.) (2016) Financial market history: reflections on the past for investors today. London: CFA Institute Research Foundation.