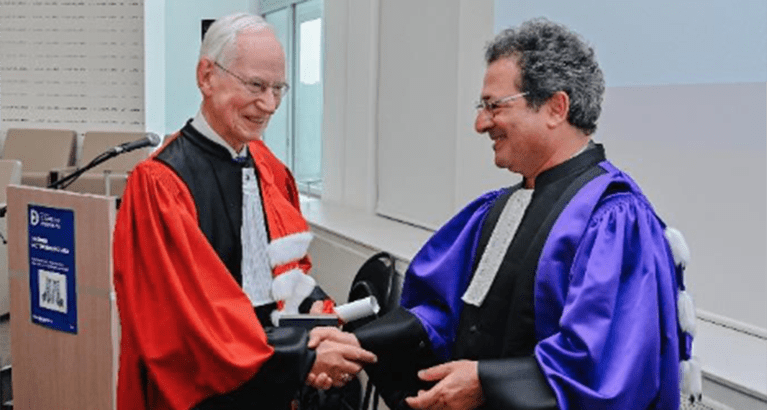

He was given the award by Professor Bruno Bouchard, Vice-President of the Scientific Council, and Professor El Mouhoub Mouhoud, President of Dauphine – PSL. Dauphine-PSL is the only institution of higher education in France that is both a grande école and a university. Dauphine is one of the founding members and constituent college of Paris Sciences et Lettres University, renowned for its teaching in finance, economics, mathematics, law and business strategy.

The award was given to David and 3 other international scientific personalities for the excellence of their research work and for their fruitful collaborations with the university. The title of Honorary Doctor is one of the most prestigious distinctions awarded by French higher education institutions. This title honours “personalities of foreign nationality for outstanding services rendered to science and technology, literature and the arts, to France or to the institution of higher education that awards the title”. Previous economists awarded the degree include John Campbell, Oliver Hart, Paul Joskow, Hayne Leland, Edmund Phelps, Myron Scholes and Robert Shiller.

Professor Anna Creti made a short presentation of the case for the honorary doctorate, which was then presented by Professor El Mouhoub Mouhoud.

Read David Newbery’s acceptance speech

Thank you for all the kind words, and especially for conferring this honorary doctorate. I value this particularly highly. I have been visiting Dauphine and working with CEEM long enough to recognise their excellence and important contributions. I do not wish to inflict my limited school-boy French on you so I apologise for speaking in English.

The laws of physics that govern how electricity flows around networks are the same world- wide, but markets vary widely across countries. There is value in studying one country’s electricity market, but even more in learning from other country’s experiences. For that, academics benefit from active contact with their colleagues studying different countries and market designs. CEEM is an outstanding example of collaborative learning across the world.

Our own Energy Policy Research Group (EPRG) at Cambridge is proud to have a direct link to CEEM. Fabien Roques is a former PhD student, a current Associate Researcher, and through his company affiliation, a financial supporter of our conferences.

CEEM, like EPRG, has established its international reputation through rigorous independent research and interactions with industry and policy makers. It publishes papers that inform public and private sector decision-making in the industry, and holds meetings where experts from academia, industry and stakeholders can exchange their views.

The Chair’s immediate concern is “to realise an ambitious research program on European electricity markets”, an interest EPRG shares. Although Britain is an isolated system with its own market design and, alas, no longer part of the European Union, we are linked to Europe by gas pipelines and electricity interconnectors.

The current energy crisis reminds us all that we inhabit the same world and suffer the same shocks. While the world is fracturing geopolitically, we should remind ourselves that we are also united in our national commitments to climate change action, set out here in Paris in 2015 and annually reaffirmed and strengthened.

The energy crisis is a timely reminder that energy policy research requires an interdisciplinary approach. Policy-making is the art of the possible, and what is possible has many dimensions – respect for the laws of physics and the laws of the country, balancing efficiency and fairness, the potential and difficulties of international agreement, for fair arbitration of breach of contract, and the moral imperatives enshrined in conventions and treaties, all of which take us far beyond narrow economics.

More than in most research endeavours, we need open discussion to bring different perspectives to the table, and groups like CEEM take this very much to heart.

Engineers design ways to balance electrical systems millisecond by millisecond. In Paris we are connected to the largest machine in the world –700,000 MW of generation perfectly synchronised and rotating as one single machine. A single machine, but one connected to 400 million voting customers. Here in Paris, Marcel Boiteux was head of EdF, an economist and mathematician who recognised that setting tariffs required new economic techniques. His approach to tariff design is now recognised as one of the foundational contributions to modern public economics theory. That theory can guide equitable ways of financing the increasing share of fixed costs in the future low-carbon electricity market. Cost allocation and cost causation cease to be self-evident bases for setting tariffs once equity and fairness are taken into account – a lesson well-known in tax theory but often overlooked by governments designing energy policy.

I greatly enjoy working with colleagues at CEEM discussing the design of the future European electricity market. Much of that enjoyment is that we reached a remarkable degree of agreement on the nature of the problem and possible solutions. We need to remember that the creation of the Integrated Electricity Market dates back to the wave of liberalisation and privatisation in the 1990s. That decade was special – there was excess generation capacity, abundant cheap gas, and a new gas turbine technology that was simple for new entrants to finance. Moving from coal in the UK to gas also delivered dramatic decarbonisation. But in the last thirty years the world has massively changed. Enthusiasm for an energy-only market to enable seamless cross-border competition has given way to concern on how to ensure that capital-intensive renewables and nuclear power can be delivered in time.

The good news is that renewable costs are tumbling, and the real cost of finance has never been lower. The bad news is that the current market design with its patchwork of fixes for renewable support and carbon pricing is no longer fit for purpose. To meet our carbon targets the industry has to double its renewables capacity by 2030, now less than 8 years away, while aging nuclear stations are being phased out.

There is considerable agreement about the key elements of the future market design – competition in the spot market that requires efficient short-run prices, but competition for the market to support new investments through auctioned well-designed long-term contracts.

There are important details to clarify where good economic, financial and public finance theory will be needed. I have proposed a new type of contract for wind and solar that hedges risk almost perfectly while still exposing them to efficient spot prices. With colleagues in the Cambridge Business School we have, I think successfully, argued for a Regulatory Asset Based finance model for our next nuclear power station.

In Britain we are pushing for nodal pricing and a return to central dispatch – possibly a step too courageous for the EU. We continue to press for a better way of pricing carbon than the ETS, which is currently amplifying the gas price impact on electricity prices.

With our European colleagues we are concerned that short-run responses to the invasion of Ukraine and the dramatic impact on oil and gas prices should not hamper moves to a better long-term enduring energy market design. Balancing short-run emergency action with future proofing requires a deep understanding of the way markets and politics work and interact.

I want to conclude by stressing the value of analytical and empirical research for energy policy that is characteristic of CEEM’s purpose and activity. Energy policy research, in contrast to often dubious macro-economics, tends to be undervalued by professional economists but it relies on, and makes substantive contributions to, economic theory, as Marcel Boiteux demonstrated. My first theoretical work on electricity markets (with Richard Green) applied supply function theory to the newly privatised English electricity industry that created a price-setting duopoly with substantial market power. Our research suggested creating five companies would deliver a competitive outcome, confirmed by later developments.

Risk and risk allocation are underappreciated by policy makers. Fabien Roques wrote an excellent PhD on the special risks facing the finance of nuclear power. The cost of risk is also often poorly understood. Many assume that it cannot be reduced but merely reallocated.

Economic theory shows this to be false. Good contract design can reduce risk while preserving sufficient incentives to manage it. I have already mentioned the new finance model for our next nuclear power station which, by a better allocation of risk, could almost halve the cost of its power. Finally, public economics, as Marcel Boiteux demonstrated, can guide equitable ways of financing the increasing share of fixed costs in the future low-carbon electricity market. Let me end by saying that we face challenges in making the transition to net zero, but they also offer wonderful opportunities for research groups like CEEM to make really valuable contributions to the policy debate, and to making that transition fairer and less costly than might otherwise be the case. Thank you.

Featured faculty/academic

[Note: use reusable block if one exists, if not use the format below – delete this note once you’ve actioned]

Name of faculty (hyperlink this) [H3 heading size medium]

Job title of faculty member

Featured research

Surname, A., Surname, B., and Surname, C. (YYYY) “[Name of paper in sentence case (hyperlink the name including quote marks)]” [Journal name in title case]

Related content

Add description ensure any links to external sites are linked inline – we don’t want to add too much attention to these as we want to reduce the bounce rate from our site.

Featured faculty/academic

[Note: use reusable block if one exists, if not use the format below – delete this note once you’ve actioned]

Name of faculty (hyperlink this) [H3 heading size medium]

Job title of faculty member

Featured research

Surname, A., Surname, B., and Surname, C. (YYYY) “[Name of paper in sentence case (hyperlink the name including quote marks)]” [Journal name in title case]

Related content

Add description ensure any links to external sites are linked inline – we don’t want to add too much attention to these as we want to reduce the bounce rate from our site.

Featured programme/Centre

Short programme/Centre description.

[Note: use reusable block if one exists, if not use the format below]

Featured programme/Centre

Short programme/Centre description.

[Note: use reusable block if one exists, if not use the format below]