Green energy and government action

El-Erian Institute of Behavioural Economics and Policy (EEI): Starting with your most updated view about green energy – how do you think governments could promote climate justice?

Professor Cass Sunstein (CS): Given where the United States is today, I feel a bit like I have written a book about folk music the week after Bob Dylan went electric. If you don’t get the reference, see ‘A Complete Unknown’, the fantastic movie about exactly that.

Still, 2 ideas:

- Use the global social cost of carbon, not the domestic social cost of carbon. That’s technical stuff, but it would mean that governments and companies would do more to reduce emissions, because they would consider the harms done to other countries in deciding how much to scale back. By the way, the global social cost of carbon is in the vicinity of £150.

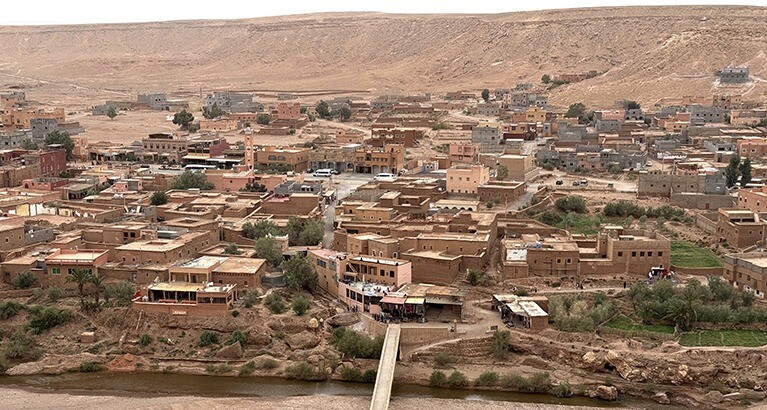

- Wealthy countries should help poor countries to adapt to what is here and getting worse. On (2), I will just say that wealthy countries are most responsible for the problem of climate change, and poor countries are suffering most from it.

Behavioural economics and climate justice

EEI: Your previous work with Richard Thaler on ‘nudges’ revolutionised how we think about behavioural change. How does that framework apply to climate justice?

CS: Mostly the climate justice issue is about justice, not nudges. It is about the obligations of all of us to future generations, and about the obligations of wealthy nations to poor ones. It is about John Rawls and John Stuart Mill, not about Richard Thaler or Daniel Kahneman. But ‘Choice Engines’, informed by behavioural economics, can help people to make better choices, included more just choices. (You’ll have to read the book to see!)

EEI: You’ve written about ‘availability cascades’ in the past – how certain risks become amplified through social dynamics. How does this concept apply to climate justice?

CS: Well, if there is a terrible heat wave or flood, people might get more activated by climate change and the risks it causes. Public concern can be activated if an event is cognitively ‘available’, and then social cascades can occur, getting people to focus on the dangers.

EEI: Your term as Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs gave you insight into how government policy is made. How can regulatory approaches balance climate urgency with justice concerns?

CS: There is politics, and there is analysis. The latter requires a focus on costs and benefits. But we also need to focus on who is helped and who is hurt. If poor people are battered by climate change, it’s a really good idea to help them.

EEI: How do behavioural insights help us understand opposition to climate policies, particularly when that opposition comes from communities that may benefit from climate action?

CS: Four ideas:

- present bias really matters – people focus, often, on the short term

- there’s also inertia, which favours the status quo

- optimistic bias plays a role

- people are loss averse, and climate policies sometimes inflict losses, certainly in the short term

EEI: Your work often explores the tension between technocratic expertise and democratic values. How does this tension manifest in climate justice?

CS: If the technocrats say that we need to scale back emissions, and if the public is cautious about that, we certainly have some tension there. On justice, we need to know what the public wants; it may or may not want to help people who are at risk in (say) poor countries. The technocrats have a lot to say about what works and what doesn’t, but justice, as such, is not their usual focus. That’s okay, but the system needs to focus on justice too.

Business leaders and climate justice

EEI: How should business leaders think about climate justice? Is this primarily a concern for governments, or do private actors have responsibilities as well?

CS: Both! A wealthy company that has contributed to the climate problem should find ways to scale back and should consider helping people who are most vulnerable. The United States and the United Kingdom, for example, need friends, and so do US and UK companies. China and Russia are competing fiercely for allies, with both carrots and sticks. If the United States, the UK and their companies help people in poor nations with respect to climate-related risks, there will be real dividends, certainly in the long-run and probably in the short-run, too. Assistance in combating the risks of climate change is not a matter of foreign aid or charity. It is a matter of justice. And there is good news. Much of the time, those who act justly end up being rewarded for their efforts.

Key takeaways

1. Future generations matter

People born in 2040 are not worth less than people born in 1990. A discount rate should reflect the fact that investments can be made to grow – not a judgment that future people matter less than current people.

2. Use the social cost of carbon, and a global one rather than a domestic one

This is the most important number most people have never heard of. The social cost of carbon is the damage done by a ton of carbon emissions. In making choices, nations and companies should use the global figure, which is around £150.

3. Choice engines can help

Choice engines, informed by behavioural economics and AI, can help people to make better choices, including more just choices.

4. Wealthy nations have moral obligations

Wealthy nations, and companies and individuals who work there, owe moral duties to people in poor nations, who are especially at risk.

5. ‘Nudges’ should be equitable

Design interventions that help people make climate-friendly choices while ensuring benefits are distributed fairly across society.

6. Nations and companies should consider effects across time and space

Business models that align immediate incentives with long-term climate benefits can help overcome this challenge.

Featured research

Sunstein, C.R. (2025) Climate justice: what rich nations owe the world – and the future. MIT Press

Thaler, R.H. and Sunstein, C.R. (2009) Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. Penguin