Overview

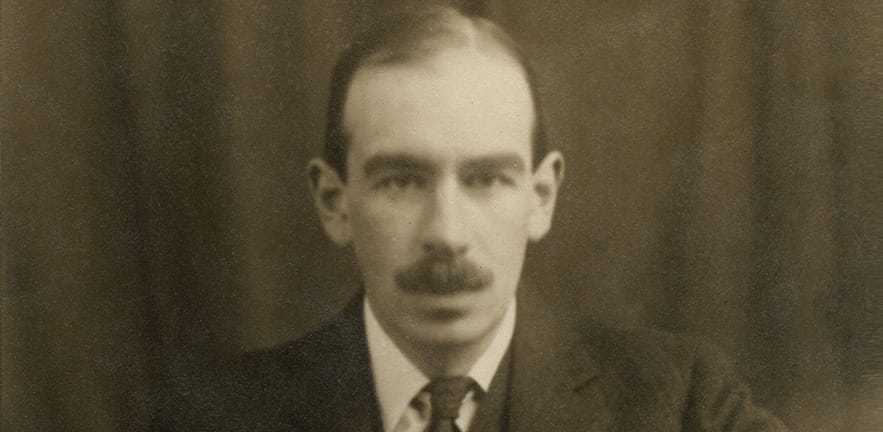

Researchers at the Centre for Endowment Asset Management, Cambridge Judge Business School, led by Dr David Chambers, are working on a large scale project that explores the investment activity of John Maynard Keynes, as a stock investor, currency trader and art investor. The research analyses Keynes’ remarkable investment record both as a private investor and as the Chief Investment Officer of Kings College Cambridge over a period of a quarter of a century.

Born 5 June, 1883 in Cambridge, Keynes was an investment innovator. During his lifetime he made a major contribution to the development of professional investment management. In addition to stocks, he traded currencies at the very inception of modern forward markets, as well as commodity futures. He was among the first institutional managers to allocate the majority of his portfolio to the then alternative asset class of equities. In contrast, most British (and American) long-term institutional investors at that time regarded ordinary shares or common stocks as unacceptably risky and shunned this asset class in favour of fixed income and real estate.

The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.

Keynes the investor

Beginning as a top-down portfolio manager, Keynes sought to time his allocation to stocks, bonds and cash according to macroeconomic indicators. He evolved into a bottom-up investor from the early 1930s onwards picking stocks trading at a discount to their ‘intrinsic value’, a term coined by Keynes. Subsequently, his stock portfolios began to outperform the market on a consistent basis.

Keynes also had a love of art and was interested in art as an investment. He built up a fine collection of art over his lifetime, which upon his death passed to King’s College, Cambridge, together with major items housed at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Although Keynes is known as a great economist, very little is known about Keynes as an investor. An almost-complete record of Keynes’ trading activity, which has until recently remained dormant in the King’s College Archives, offers a rich resource to utilise and reconstruct Keynes’ investment decision-making.

[MUSIC PLAYING] David Chambers’s interest in John Maynard Keynes began over a decade ago. During his research of Keynes, he interviewed historian and Keynes biographer Lord Robert Skidelsky. That discussion prompted his further investigation into Keynes’s varied investment portfolio.

Having met Skidelsky, that set me off on a bit of a hunt. I at that time was not in Cambridge initially, but I came up to Cambridge, went to the King’s College Archive, and after ferreting around for a few days with the great assistance of the archivist, I was actually able to find the documentary evidence, and that specifically was of three kinds. It was the actual portfolios so the portfolio evaluations, which would have taken place every year, and then in-between times, the transaction sheet, which told you how many shares or securities he bought and sold on a particular date at what price. And then the third type of evidence was the voluminous correspondence that he wrote with two other people backwards and forwards dealing with investment matters.

Initially, we set off looking particularly how he managed the College endowment, King’s College Cambridge endowment, and specifically how he managed the stock portfolio. It also became apparent that he was managing currency, so he was investing in currencies through the 1920s and ’30s, and as well as investing in commodities. And then the fourth area we uncovered was his art collection. Each of those four different areas– stocks, currencies, commodities, and art– have been terribly revealing about what he did. First up is how he traded stocks and also how he traded currencies proved him to be an exceptionally innovative investor.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Keynes the stock investor

Keynes’ UK stock portfolio out-performed the overall stockmarket by an average of 8 percentage points each year. However, Keynes struggled in the 1920s and it was only after he radically shifted away from a top-down, market-timing to a buy-and-hold, stock picking approach in the early 1930s that his performance improved dramatically.

Keynes stayed true to his commitment to equities. When the London stock market fell sharply in 1937-1938, he resigned as chairman of an insurance company – one of several financial institutions with which he was associated – when the rest of the board were unwilling to stick with his strategy.

Following the 1929 Wall Street Crash, Keynes, having suffered heavy losses, sold a fifth of his UK equity holdings and switched investments into government bonds – an understandable and conventional response. But when the market declined sharply again in August 1937, he instead made some modest additions to his UK equity positions and maintained his overall equity allocation at above 90%.

Keynes’ strategy was also informed to some extent by his personal network, including senior managers within some of the companies in which he invested. This has led some to suggest he may have benefitted from insider trading, which was not illegal at the time. Chambers and Dimson argue that even if Keynes did make use of what today would be regarded as private information when monitoring his favourite stocks, he did not do so for short-term gain.

Chambers suggests that Keynes techniques should encourage today’s investment practitioners, especially those with a relatively long time-horizon, to have similar confidence in their investment decisions.

[MUSIC PLAYING] In the case of stocks, the main point was that he was really the first person in an institutional context, or certainly, in the context of someone running long-term assets like endowment portfolios, he was the first investor to embrace investing in stocks as opposed to bonds or real estate. He started trading currencies as soon as the forward market in London, the forward exchange market, became established in 1919.

In the case of commodities, this is actually one of the latest bits of research that we’re doing, and we still haven’t quite figured out what he’s doing with his commodity trading, other than that he’s doing a lot of it and appears to be employing some– again, some very interesting strategies. One of the interesting questions about Keynes is that given that, whilst overall, he was successful in the way that he invested, he did have to withstand periods when either he incurred substantial losses or he went through periods of underperformance.

And the question is, why didn’t he– why didn’t he quit? And I think the single biggest reason for that is that he was just as a tremendously self-confident individual, I mean, intellectually self-confident. I think it would be correct to say that he was intellectually arrogant. I mean, he had– obviously he was a– he was an extremely clever person.

He had very little time for other people who he didn’t think were intellectually on his level. But if he thought on a particular subject, you had something to contribute, then he would pay the utmost attention to you.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Successful investing is anticipating the anticipations of others.

Keynes the currency trader

Research into currency trading during the 1920s and 1930s reveals the existence of substantial profit opportunities for currency speculators during this period. Keynes actively invested in stocks for his Cambridge College, he also traded stocks for himself and this raises the question of whether he engaged in hedging the currency exposure of his stock portfolio.

Although Keynes did not invest in any European stocks, his shorting of European currencies was not at all related to currency hedging needs. His personal stock portfolio was entirely invested from 1919 to 1923 in UK stocks and from 1924 to 1927 he only had a very small 3% allocation to US stocks. Between 1932 and 1939, his average allocation to US stocks increased to 34% of his stock portfolio. He began his career as a currency speculator with a high level of confidence; however his confidence in his exchange rate forecasts faded over time.

Research analysis of Keynes’ correspondence and memoranda from the 1930’s indicate he became increasingly pessimistic, as he realised the great difficulty in predicting currency movements.

The research provides a number of examples of how he derived his views on a currency from his evaluation of its underlying fundamentals, however there were no examples indicating the possibility that he followed simple technical trading rules.

Keynes achieved positive cumulative profits over both periods he traded and appeared to possess skill in predicting exchange rates over long horizons, however the research concludes, he would have achieved higher profits in the 1920s if he had followed simple technical trading strategies rather than his own discretion.

[MUSIC PLAYING] Turning to his currencies, his performance was much more chequered. Again, overall, he made money, but he really had to endure periods of time, most notably in 1920, where he lost an awful lot of money. This performance I’m talking about is the performance for himself for his own personal portfolio.

He was not trading currencies for his college in the 1920s when he was trading for himself. He did trade currencies for his college in the 1930s, I think, when he felt he was on more certain ground, as well as trading currencies for himself in the ’30s. So overall, we can get a better picture for his currency trading performance by looking at what he did on his own account, his personal account.

So in 1920, he lost a huge amount of money in May 1920 because his positions went wrong. And it’s thought he was on the verge of personal bankruptcy. However, what did he do? If it had been you or I, we would have quit trading and gone back to our day job. He went out and borrowed some money from an aristocratic friend of his, and actually invested that money in the very same positions, the same trades. By the end of the year, he’d recovered his losses. And throughout the rest of the 1920s up to 1927, he overall made money. Then, again, in the 1930s, he initially lost money for the first three years before he finally made money. And overall, he made money.

So you can tell from that description that whilst overall he made a positive return, his returns were extremely volatile. And that the great difficulty– and again, he wrote about this later on in the 1930s. The great difficulty he faced when he was trading currencies is that directionally, he had skill in forecasting the direction of a currency correctly, but he had great difficulty in judging the timing of when to jump into either buying or selling a currency. And so very often, he was too early. And that meant he had to endure losses before he was able to make big profits. And that is a problem which modern currency traders also would confront.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Economics is a very dangerous science.

Keynes the art investor

John Maynard Keynes’ many writings on the stock market are well-known. As well as being fascinated by financial markets and economics, Keynes was attracted to the arts. He was an avid collector of artwork, books, and manuscripts and built up a fine collection during his lifetime. Keynes purchased artworks through various channels between 1917 and 1945.

Keynes was a lover of the arts, a stern supporter and patron of British Artists, and enjoyed the company of many creatives of this genre in his time. He was greatly influenced in his artistic tastes and collection by other members of the Bloomsbury Group – a collective of British intellectuals and artists. He was however “motivated in his purchases by the idea of art as an investment” (Scrase and Croft, 1983).

Following his death and the death of his wife Lydia, Keynes’ entire art collection was bequeathed to King’s College, in Cambridge. This collection consists of over 100 pieces by various artists, including Modern Masters such as Braque, Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Seurat. It has remained intact to the present day, with the pictures being hung at the College and at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

[MUSIC PLAYING] Looking at his art collection, what became apparent to us there is that he was not only collecting art for the sheer joy of owning beautiful pictures, but he was also regarded art as an investment. It looks like he did make a considerable amount of money for his college. Again, the art collection was something that he built for himself. So this was in his personal assets when he died. But upon his death, he bequeathed the art portfolio to his college. So now, the art collection belongs to the college.

But overall, from the time when he bought these pictures, which was during his lifetime, he bought his first picture in 1918 and continued to buy pictures through the rest of his life up to his death in 1946. If we measure the returns from that collection up till the present day, then they are roughly in line with the return you could have got on the UK stock market. Which for an art collection is very respectable indeed.

Insights and resources

Media coverage

Forbes | 22 January 2016

Why currency trading is a bad idea: Keynes

John Maynard Keynes struggled as a foreign-exchange trader, finds the first detailed study of the famous economist as currency speculator. “If someone as economically literate and well-connected as Keynes found it difficult to time currencies, then the rest of us should think twice before believing we can do any better,” says co-author David Chambers, Reader in Finance and an Academic Director of the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM) at Cambridge Judge Business School.

Bloomberg View | 15 January 2016

FX traders, take heart: even Keynes lost his shirt

John Maynard Keynes struggled as a foreign-exchange trader, finds the first detailed study of the famous economist as currency speculator. “If someone as economically literate and well-connected as Keynes found it difficult to time currencies, then the rest of us should think twice before believing we can do any better,” says co-author David Chambers, Reader in Finance and an Academic Director of the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM) at Cambridge Judge Business School.

The Times | 13 January 2016

Big Short put Keynes on the brink of bankruptcy

John Maynard Keynes was ‘a financial genius whose ideas dominated western economic policy making for 50 years’, writes Patrick Hosking in The Times. But it’s little know that Keynes was also trading in foreign currency. The latest study co-authored by David Chambers, Reader in Finance and Academic Director of the Newton Centre for Endowment Asset Management at Cambridge Judge, found that Keynes struggled as a foreign-exchange trader.

The Guardian | 12 January 2016

John Maynard Keynes ‘a great economist but poor currency trader’

A study co-authored by Elroy Dimson, Research Director (Finance) and Chairman of the Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM) at Cambridge Judge Business School, is mentioned in this article about small-cap stocks.

Financial Times | 5 September 2014

How to see into the future

“John Maynard Keynes’s track record over a quarter century running the discretionary portfolio of King’s College Cambridge was excellent, outperforming market benchmarks by an average of six percentage points a year, an impressive margin.” David Chambers, University Lecturer in Finance, and Elroy Dimson, Research Director (Finance & Accounting), at Cambridge Judge Business School, discuss their study.

Financial Advisor | 2 June 2014

Keynes’ way to wealth

John Wasik investigates why John Maynard Keynes is one of the most important economists in history and refers to research by David Chambers, Director of the CJBS Centre for Endowment Asset Management and Elroy Dimson, Co-Director of the Centre for Endowment Asset Management (CEAM).

New York Times | 10 February 2014

John Maynard Keynes’ own portfolio not too dismal

Reporter John Wasik investigates influential economist John Maynard Keynes’s approach to investing in research by David Chambers, Director of the CJBS Centre for Endowment Asset Management and Elroy Dimson, Co-Director of CEAM.

The Daily Telegraph | 26 October 2013

How to invest like… J. Maynard Keynes

The influential economist also happened to deliver annual returns of 15pc in a timespan covering the Wall Street Crash and the Second World War, writes Andrew Oxlade. In a newly published study of Keynes’s investments for King’s College, Cambridge, Dr David Chambers, university lecturer in Finance, and Professor Elroy Dimson, research director in Finance and Accounting of Cambridge’s Judge Business School, acknowledges Keynes’s idiosyncratic style.