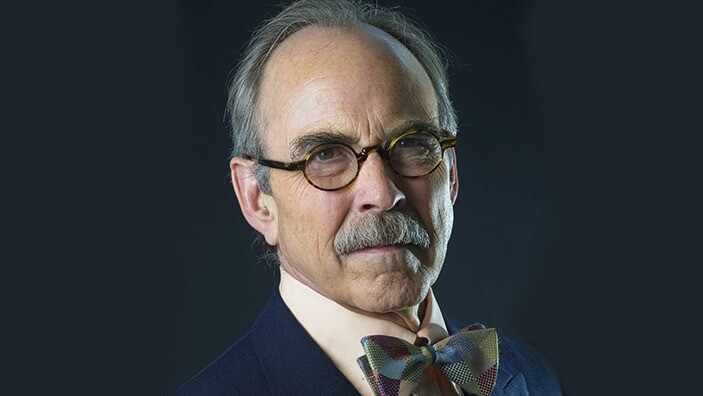

Ambassador for Cambridge Judge Business School

Senior Advisor & Managing Director, Warburg Pincus

Dr William H Janeway is a Senior Advisor and Managing Director of Warburg Pincus. He joined Warburg Pincus in 1988 and was responsible for building the information technology investment practice. Previously, he was Executive Vice President and Director at Eberstadt Fleming. Dr Janeway is a director of Magnet Systems, Nuance Communications, O’Reilly Media, and a member of the Board of Managers of Roubini Global Economics. He is a Visiting Lecturer in Economics at the University of Cambridge and Princeton University.

Professional experience

Dr Janeway is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Cambridge in America, University of Cambridge and a Member of the Board of Managers of the Cambridge Endowment for Research in Finance (CERF). He is a member of the board of directors of the Social Science Research Council and the board of governors of the Institute for New Economic Thinking and of the Advisory Boards of the Princeton Bendheim Center for Finance and the MIT-Sloan Finance Group. He is the author of Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy: Markets Speculation and the State, published by Cambridge University Press in October 2012.

Dr Janeway received his doctorate in economics from the University of Cambridge, where he was a Marshall Scholar. He was valedictorian of the class of 1965 at Princeton University.

News and insights

Insight

A time to venture?

High risk and a leap in the dark – venture capital isn't for everyone. How can anyone seeking to invest in it gain a better understanding of the risks and potential rewards? For the investor who wants to add a bit of spice to their dealings, venture capital looks like the perfect solution. The risks are sufficiently vertiginous to satisfy any adrenaline junkie – and the returns can be astonishing. Take Google, the small technology firm that two venture capital firms (Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers and Sequoia Capital) paid around $25m for a 20 per cent share of in 1999, and which now has a market capitalisation of more than $556bn. But assessing the possible returns of venturing capital is not straightforward. The very concept of an "average" return is meaningless: while the occasional huge success can deliver stratospheric returns, most investments fail or succeed only to a modest extent. So if the chances of striking it that lucky are low, easier access to data for returns on a broader range of venture capital investments could at least help identify factors that might highlight the talents of fund managers able to make wise investment choices. It would also enable…

Governance, economics and policy

Does economics need less maths or more?

Has mathematics become too complex and too dominant a force in modern economics? Yes, says Cambridge Judge Business School's Michael Kitson; no, says economist Dr William H Janeway. Here both experts set out their views on what's needed to help avoid a repeat of the recent financial crisis.

Insight

Model behaviour

I do not believe that economics went wrong because of using mathematical models. It's more complicated than that. The first question is whether it is possible to understand complex processes without to some extent constructing models. Any attempt to examine the dynamic relationships and interdependencies within a complex system is going to require simplified models that isolate some elements from the whole, so that they can be examined with rigour. In fact, the problem with economics is that the maths has been too simple. The mathematics adopted by economists from statistical mathematics in the late 19th century required radical simplification: the construction of homo economicus, the 'rational' maximising agent in an economics abstracted from the other social sciences and from society and culture. Now economics is the most data-rich of the social sciences, because it's largely about transactions. So it lends itself to quantification and statistical analysis. In turn, any such analysis requires deployment of an underlying model. The more realistic the assumptions about human behaviour and the social context – about the dynamics of people interacting with each other – the more challenging the maths has to become. So to have realistic models requires more maths, not less maths.…